WHAT RULES THE WORLD?

Years ago, when touring dino-mation exhibits were all the rage, my parents took me to “see the dinosaurs” at the Morris Museum. I was terrified. I had seen dinosaur skeletons before, but the moving, roaring beasts sent me scurrying around the corner, peeking around it as if from a blind. My father walked up to a Triceratops and touched it to show me I was safe, but even though I was so excited about seeing dinosaurs I could not contain my fear when confronted with them face-to-face. This strange mixture of fear and fascination is not unique to children; we admire fierce predators but we wouldn’t want to stumble upon one in some dark wood or inky sea. While bears, cougars, and sharks elicit such feelings today, dinosaurs also inspire fear & fascination. They are both dangerous and safe, and it is of little surprise that ancient bones have long inspired people from various background to contemplate antediluvian monsters and prehistoric killers.

Perhaps no early popularizer of paleontology is as celebrated as William Buckland. Cuvier may have made paleontology a science, and Richard Owen may have coined the term “dinosaur,” but it was Buckland who most effectively “burst the limits of time” in both scientific and popular circles. While merely being an anecdote, Henry Acland’s description of Buckland’s lecturing style gives us some appreciation for his combining science with showmanship;

“He lectured on the Cavern of Torquay, the now famous Kent’s Cavern. He paced like a Franciscan Preacher up and down behind a long show-case, up two steps, in a room in the old Clarendon. He had in his hand a huge hyena’s skull. He suddenly dashed down the steps– rushed, skull in hand, at the first undergraduate on the front bench–and shouted, ‘What rules the world ?’ The youth, terrified, threw himself against the next back seat, and answered not a word. He rushed then on me, pointing the hyena full in my face–‘ What rules the world ?’ ‘Haven’t an idea,’ I said. ‘ The stomach, sir,’ he cried (again mounting his rostrum), ‘ rules the world. The great ones eat the less, and the less the lesser still.’ ” [From The Life and Correspondence of William Buckland]”

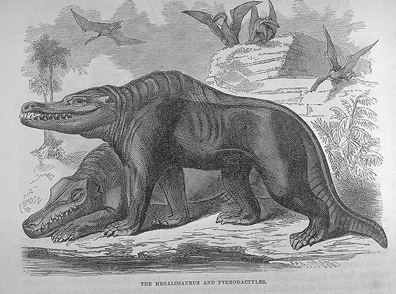

The Kirkdale cave hyenas made Buckland a scientific superstar, but he is most often discussed today in context of his identification of the dinosaur Megalosaurus. As related by his son Francis, the elder Buckland played up the seemingly fantastical nature of prehistoric animals. From Francis Buckland’s Curiosities of Natural History;

“During this period of monsters there floated in the neighborhood of what is now the lake of Blenheim – huge lizards, their jaws like crocodiles, their bodies as big as elephants, their legs like gate-posts and mile-stones, and their tails as long and as large as the steeple of Kidlington or Long Habro’. Take off the steeple of either church, lay it in a horizontal position, and place legs on it, and you will have some notion of the animal’s bulk. These stories look like fables, but I ask not your indulgence to believe them. There the monsters are, and I challenge your incredulity in the face of the specimens before your eyes; – disbelieve them if you can.”

While the phrase “the struggle for existence” is most closely associated with Charles Darwin, the idea of the ancient past as a violent world filled with monsters is nearly as old as paleontology itself (see Adrienne Mayor’s The First Fossil Hunters and Paul Semonin’s American Monster). The remains of animals wrested from the earth represented terrifying creatures far grander than any living form, and it was often thought that their extinction was tied to their destructive, carnivorous habits. It may seem strange, then, that casting fossil creatures as monsters and dragons was juxtaposed with natural theology, the perfection of killing claws and crushing jaws being tied to the beneficence of an all-wise Creator (although such appeals most often appeared in popular works, theology being increasingly pushed into the background and geology came into its own).

Indeed, prior to the discovery of dinosaurs mammalian behemoths fired the imaginations of professionals and members of the public alike. The remains of the American mastodon and giant ground sloth Megalonyx were interpreted to denote the presence of carnivorous terrors when they were initially discovered, only later being recognized as the teeth and bones of herbivores. In 1797, George Turner proposed that the animal we now recognize as the mastodon may have sprung upon unsuspecting prey, then devouring the mangled carcasses of the victims (as reproduced in Hedeen’s Big Bone Lick);

“It is well known that the buffalo, deer, elk, and some other animals, are in the constant habit of making such places [as Big Bone Lick] their resort; in order to drink the salt water and lick the impregnated earth. Now, may we not from these facts infer, that Nature had allotted to the Mammoth the beasts of the forest for his food? How can we otherwise account for the numerous fractures that every where mark these strata on bones? May it not be inferred, too, that as the largest and swiftest quadrupeds were appointed for his food, he necessarily was endowed with great strength and activity? – that, as the immense volume of the creature would unfit him for coursing after his prey through thickets and woods, Nature had furnished him with the power of taking it by a mighty leap? – That this power of springing to a great distance was requisite to the more effectual concealment of his bulky volume while lying in wait for prey? The Author of existence is wise and just in all his works. He never confers an appetite without the power to gratify it.”

Considerations about the beneficence of God (both in endowing the monstrous mastodon the ability to catch prey and wiping such a horribly predator off the face of the earth) certainly colored the way ancient animals were reconstructed, but this alone cannot account for the ongoing fascination with prehistoric animals as monsters. Their size, perceived strength, and overall bizarre characters have continually led people from all background to wonder what the stone bones must have been like when they were covered with flesh and sinew.

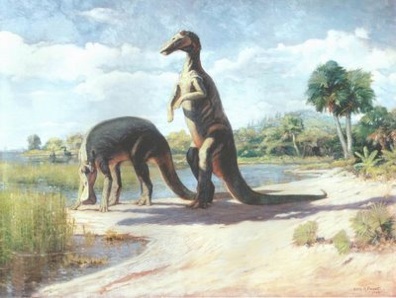

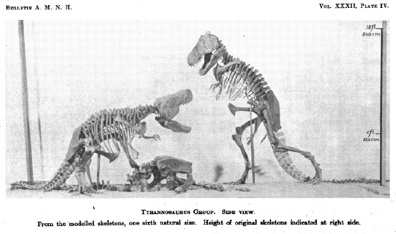

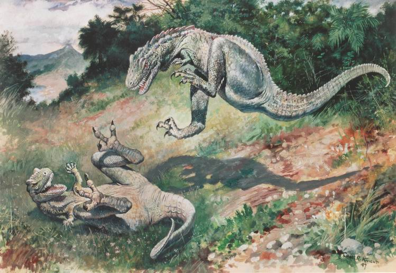

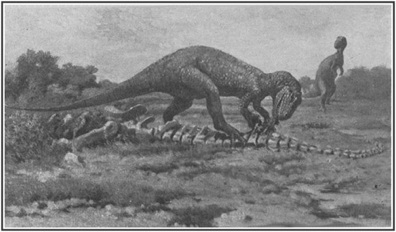

The sensationalism that surrounds prehistoric creatures is still with us today, although scientific studies have somewhat tempered the more poetic and wildly imaginative representations that were more prominent in the 19th century. As paleontology came into its own as a science, ancient beasts uncovered by bone sharps like Charles Sternberg and Barnum Brown still received fantastic popular treatments, the skeletal mounts at the AMNH attempting to represent what the animals might have been like in life. The Allosaurus mount, for instance, is depicted as being in the act of rending the flesh from a skeleton of Apatosaurus, and an upright Anatotitan was envisioned as being on the lookout for predators. The most striking mount was never produced, though, H.F. Osborn and Barnum Brown hoping to create a “clash of the titans” type reconstruction of two Tyrannosaurus. Brown described the scene as follows;

“It is early morning along the shore of a Cretaceous lake three millions of years ago. A herbivorous dinosaur Trachodon venturing from the water for a breakfast of succulent vegetation has been caught and partly devoured by a giant flesh-eating Tyrannosaurus. As this monster crouches over the carcass, busily dismembering it, another Tyrannosaurus is attracted to the scene. Approaching, it rises nearly to its full height to grapple the more fortunate hunter and dispute the prey. The crouching figure reluctantly stops eating and accepts the challenge, partly rising to spring at its adversary. [As quoted in Desmond’s The Hot-Blooded Dinosaurs]”

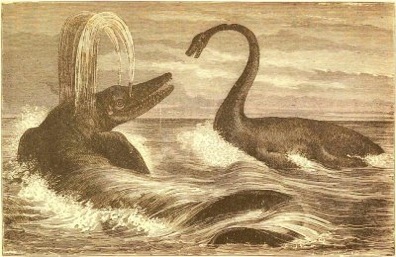

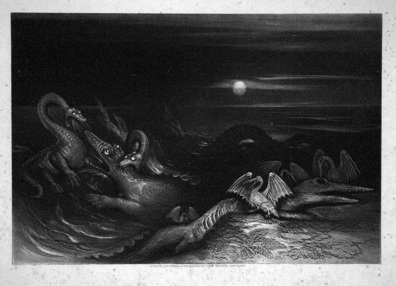

Dinosaurs were not the only Mesozoic creatures to spark such imaginative restorations. In his autobiography The Life of a Fossil Hunter, C.H. Sternberg imagines an ancient Cretaceous sea in which mosasaurs battle to the death;

“But before we return to civilization, will my readers go with me on another expedition to these Kansas-chalk beds? “How fleet is a glance of the mind!” Instead of an arid, treeless plain, covered with short grass, a great semi-tropical ocean lies at our feet. Everywhere along the shores and estuaries are great forests of magnolia, birch, sassafras, and fig, while a vast expanse of blue water stretches southward.

“But,” you ask, “what is that animal at full length upon the water in that sheltered cove?”

Watch it a moment! It raises a long conical head, four feet in length and set firmly upon a neck of seven strongly spined vertebrae. This powerful head terminates in a long, bony rostrum, also conical in shape. Back of the neck are twenty-three large dorsal vertebrae, followed by six pygals, as Dr. Williston calls them, to which the hind arches and paddles are attached. They body terminates in an eel-like tail of over eighty elements, each strengthened by a dorsal spine above and a V-shaped bone, called a chevron, below; so that a vertical section of the lizard would have a diamond shape.

But see! an enemy in the distance is attracting our reptile’s attention. It sets its four powerful paddles in motion, and unrolling its forked tongue from beneath its windpope, throws it forward with a threatening hiss, the only note of defiance it can raise. The flexible body and long eel-like tail set up their serpentine motion, and the vast mass of animal life, over thirty feet in length, rushes forward with ever-increasing speed through water that foams away on either side and gurgles in a long wake behind.

The great creature strikes its opponent with the impact of a racing yacht and piercing heart and lungs with its powerful ram, leaves a bleeding wreck upon the water. Then raising its head and fore paddles in the air, it bids defiance to the whole brute creation, of which it is monarch.”

Even a less fanciful description of a mosasaur plays up the fearsome dentition (an arrangement a professor of mine once opined was like a “real-life ALIEN”) and gruesome feeding habits of Sternberg’s ruler of the “brute creation”;

“If you will look closely at the [skull], you will notice, within the head, and below the eyesocket, a row of recurved teeth. These are the teeth on the pterygoid bones, which are located on either side of the roof of the mouth, near the gullet, and are provided with twelve teeth, more or less. The lower jaw with its powerful sweep on its fulcrum, pressed the living prey firmly upon these teeth so that it could not come forward and escape. Then notice the ball-and-socket joint just back of the tooth-bearing bone or dentary, of the lower jaw. After the wriggling, struggling prey had been fastened on the teeth in the roof of the mouth, the mandibles were shortened by a spreading of the central joint, and the victim was forcibly pushed down the throat.”

H.F. Osborn, too, mixed the technical with the terrifying. On the frontispiece to his extremely dry book The Origin and Evolution of Life, Osborn’s “pet” (Tyrannosaurus rex) is featured with the caption;

“Tyrannosaurus rex, THE KING OF THE TYRANT SAURIANS. The climax among carnivorous reptiles of a complex mechanism of the capture, storage, and release of energy. Contemporary with and destroyer of the large herbivorous dinosaurs.”

This statement is very close to description E.D. Cope gave his tyrannosauroid Laelaps (later renamed Dryptosaurus by O.C. Marsh), the Cretaceous predator being “the devourer and destroyer… of all… it could lay claws on,” (from Wallace’s The Bonehunter’s Revenge). Such restorative language has fallen out of favor in professional & technical documents, however, but it still remains in popular books (especially those geared towards children that are generously illustrated). Edwin Colbert’s 1977 book The Year of the Dinosaur elaborates on the life of a female Brontosuaurs, the very first chapter featuring an attack by an Allosaurus;

“Brontosaurus now became aware of her pursuer, so she abandoned her leisurely pace and made for the far shore with all the prodigious energy at her command. Allosaurus also put on a burst of speed, in an attempt to overtake her. His effort, too, was immense, and it brought him abreast of Brontosaurus as she left the water and clambered up the beach. She was trying to reach the forest as he attacked with all of the reptilian fury at his command. His attack was bloody, but largely ineffectual. Her size was her protection: the great predator could tear at her, but he could not bring her down. So they crossed the beach, the one clumsily fleeing as the other attacked time and again, and in that manner they entered the jungle.”

Once through the jungle “Brontosaurus” spies a marsh that she slips into, shaking the predator, although if the illustration that accompanies the chapter is any indication she would have had a number of gaping wounds along her back. As noted by Colbert, this sequence was not merely a flight of fancy; it was inspired by the Paluxy tracks (a detailed account of the discovery, excavation, and early interpretations of which can be found in R.T. Bird’s Bones for Barnum Brown) which suggested a large carnivore in pursuit of a sauropod. Later writers would not allow the sauropod refuge in the water, though. In William Stout’s The New Dinosaurs, a sauropod tries to escape a pack of predators by taking to the water, the move ending in tragedy for all;

“The carnosaurs, the striders of dry land, hesitated, then took after him. At first, cranking long legs up clear of the shallow water, they gained. The land began to shelve off, giving the advantage to the tremendous power of the sauropod. He shoved along, touching the bottom with his front legs. The water deepened. Soon all had to commit their bodies to the choppy sea, and, with sinuous sweeps of their tails, they swam. All were essentially out of their element, but the sauropod fled for life while the four hunters persisted: for life, for strength, for growth, and for progeny. They exhausted each other, and bobbed for a while in the swell of the black ocean. They wheezed for air. The hunters tried to close the gap. The sauropod thrashed sluggishly ahead, leaving for them a boil of water. All floated, sucking air. The prey fought to swim clear of them; the carnosaurs wallowed after him. The nearest of them was almost within reach. The long sauropod neck coiled sideways and pressed the hunter’s head down underwater. The hunter thrashed convulsively. Lacking the instinct necessary to achieve a drowning, the sauropod let the head surface.”

As night falls, the predators and prey find themselves at the mercy of “the true denizens of the water.”;

“Yielding gracefully, the sea creatures cruised the extent of each body. Blasts of light showing only where each sea creature had been, were followed soon by thunder. The pliosaurs and cryptocleidus swooped slowly under each belly, turned and did so again. Then, finally and fatally decided, they executed the screwing half rolls which brought their jaws against the undersides of sauropod and carnosaur alike. The land animals foundered, and when the air escaped from their torn lungs, they sank.”

Stout’s book features plenty of other vignettes that are not as violent, but the conflict between predator and prey takes a prominent place among the stories and artwork. The stunning artwork of Douglas Henderson in Nicholas Fraser’s Dawn of the Dinosaurs also prominently features predator/prey conflicts, although many of the pieces are constructed as if the reader was walking through a Triassic forest or ambling along an ancient shoreline.

Much of this essay has focused on popularizations of prehistoric creatures as monsters or bloodthirsty brutes in popular settings, but predators are still celebrated within the technical literature as well. Questions about the bite forces and mechanics of Tyrannosaurus (and other theropods) have generated many papers, and one of the most publicized paleontological debates in recent memory centered around whether Tyrannosaurus was a hunter, a scavenger, or both to varying degrees. Scientific jargon and publication in journals may obscure such fascination from much of the public, but professional paleontologists are as fascinated with predators as anyone else.

Paleontology has evolved as a science, but the appeal of the “great carnivores” remains. Fierce theropods are the most popular of dinosaurs (any trip to a museum that displays a Tyrannosaurus provides ample evidence of this), and paleontological restorations often focus upon the struggle between predator and prey. William Stout’s beautiful murals recently unveiled at the San Diego Natural History Museum, for instance, feature a snarling dire wolf threatening an massive Smilodon, blood dripping from its saber-like fangs, in a scene that shares the spirit of de la Beche’s imagining of ancient Dorset (the wolves and cats are not dinosaurs, of course, but they do fit into under the umbrella of fierce extinct creatures). Modern nature documentaries further illustrate our preoccupation with violent encounters between animals; whether we’re watching a shrew catch insects or a pride of lions pile on a cape buffalo, the power and skill of predators is widely admired. The recent collection of essays Listening to Cougar reinforces this phenomenon; nearly every essay extols the terrifying strength and skill of the cat, something that we both fear and admire in this “peaceful adversary.”

I am not about to decry the use of violent clashes between the hunter and the hunted in paleontological reconstructions, be it in a museum, book, or traveling live show. The “evolutionary arms race” between predators and prey is important to natural selection, and among the scenes of theropods ripping the flesh from the bones of their victims, such reconstructions have come to punctuate presentations of prehistory rather than be the only aspect of the creatures now appreciated. Children, especially, will continue to pit plastic dinosaur against dinosaur in mortal combat in sandboxes and hunt vicious, toothy terrors in video games, and this phenomenon can be used as a draw to teach rather than presented only as gory spectacle alone. Even among professional paleontologists, the terms “dinosaur hunter” or “fossil hunter” are often used (at least as subtitles to books), although the goal is to capture and restore rather than destroy (yet this is still weilding some amount of power over the beasts).

It is impossible to look at the jaws of Tyrannosaurus and not imagine what they must have been like in action, and such daydreams (and nightmares) will continue to inspire paleontologists for years to come.