Some COVID-19 Questions From a Curious and Concerned Seven Year Old

I got this letter the other day and it’s awesome! I thought I would try my best to answer these great COVID-19 questions. Thanks Alaina!

1. Where does the virus actually come from?

Right now, the best answer is likely from one of these:

Yup, a bat.

But how it changed from a virus that infects bats to one that infects humans is still not really known. However, this sort of thing has happened before and the science word for it is zoonosis.

This is where a disease which would normally only infect an animal (in this case a bat), somehow changes so that it can also make humans sick.

Still, many scientists feel that how humans behave is partly responsible for why zoonosis happens more often than it needs to. Basically, how humans get their food and make all the things that they like to own, can lead to situations where more and more animals are forced to get “closer” to people.

For instance, getting the energy to make things usually requires cutting down trees, or digging for coal and oil, and this means that a lot of habitat is destroyed. With their homes destroyed, many animals end up in places where humans live.

And anytime you have lots of animals living with humans, you increase the chances of zoonosis. It is still a very rare thing, but hopefully it makes sense that destroying habitat is still a way to increase the chance of a disease jumping from that wild animal to humans.

Zoonosis is also a problem in how we usually get our meat (like the chicken, pork, or beef we eat). These farms or fields tend to have SO many animals in one place hanging out with people, and there have been cases where scientist have seen zoonosis happened in these situations.

2. How can the virus travel when people are less than two metres apart?

So, the virus is very very small. Like really small. Teeny tiny even.

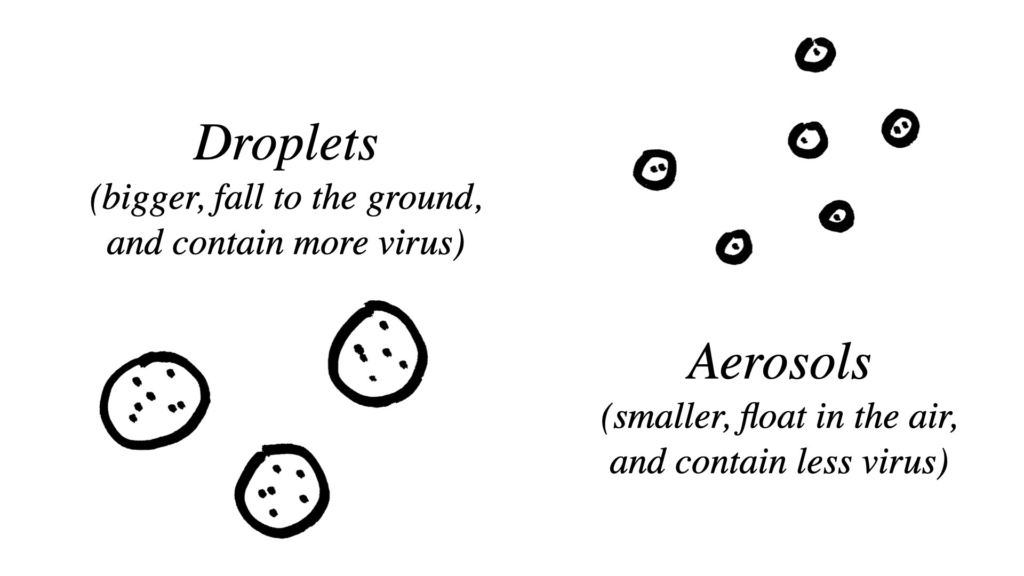

This means that the virus can travel in your spit. When it comes to travelling, science actually thinks of spit in two ways: one is called a droplet, and the other is known as an aerosol, which is a special kind of droplet.

Droplets are usually big enough that they will fall to the ground, but they are still small enough that they travel a little bit with the wind or when pushed (like breathing or a sneeze). Think of a spray bottle of water – you can see the mist, but it does fall down. So most droplets do eventually fall, and usually fall quite quickly.

Aerosols are where the droplets are very very very small. Here, some of the spit that comes out of your mouth and nose is just so tiny that it just kind of floats. This means that it can stay in the air longer and also maybe travel much further.

The 2 metres or 6 foot social distancing thing is actually from a much older science experiment done with noticing how people got sick on airplanes. Here, they noticed how people sitting close to each other were more likely to get infections. This seemed to be mostly because of droplets. In other words, the droplets would be able to spread out about 2 metres or so. It was also here they noticed that if a person was sitting more than 2 metres away from someone sick, they generally didn’t catch the disease.

For COVID-19, it’s still not exactly clear how infectious droplets and aerosols are, or even what the safe distance apart is exactly (the airplane studies were not looking at COVID-19). Yes, aerosols can travel further, but since they are smaller, they also carry less virus.

If you have less virus, then there might not be enough for the infection to start. The 2 metres and 6 foot rule is just a rough idea to make people remember that any kind of social distancing is an important thing to do.

It’s really hard to know what the exact distance should be, because it depends on so many different things. Like whether you are inside or outside; how the air around you is moving; how much virus is in the droplets (in other words, how sick is the person); what is the temperature; is the person breathing hard, and so on.

There are so many things that can affect how far the virus can transfer, but probably, you’re less likely to get an infection if you are:

(1) further apart,

(2) you are outside,

(3) you are wearing a mask, and

(4) you stay with your small group

All of these things probably make it less likely for the virus to travel from one person to another.

3. How long will the pandemic last?

4. When will the vaccine be ready?

EVERYBODY wants to know the answers to these two questions! (Note that you can read a bit more about vaccines here). Funnily enough, the answer to the first question is more or less the answer to the second question. In other words, the pandemic will end when there is a vaccine.

Because of this I’ll focus on the second question. So when will the vaccine be ready?

The answer to this is:

Or, a big fat “we don’t really know.”

Now, there are a LOT of scientists working on this now, so there is reason to be hopeful. But the reality is that making a vaccine is hard and it takes time.

Most of this time is because you always have to test whether your vaccine idea WORKS or not, and this is actually pretty complicated.

For instance, knowing whether a vaccine is able to protect someone from COVID-19 takes at least a couple months to know. It’s like you’re cooking and you’re trying some different ingredients, but you don’t get to taste it until 3 months or more later. After 3 months, you might find out that it tastes terrible or even that eating it makes you get sick! If that happens, you have to start all over again with different ingredients.

Also, you want to test it on different types of people. Young people (like you), people like your parents (moms and dads), and probably most importantly, the elderly. A vaccine may work well to protect one group but not another. A vaccine may work fine for one group but is actually dangerous for another. It takes time to figure this out, and more so because you can’t tell how things are going until many months later.

Because there are so many unknowns in how a vaccine might work, testing usually starts out with just a few people. If after a couple months, things look promising, you then do the test on more people, and so on and so on, until you get a clearer view that it is hopefully working, but that it is also safe. Again, all of these steps take time.

And this is only if the vaccine idea you’re trying works in the first place!

All scientists will tell you that science experiments are hard – it takes a lot of effort to get them to work, and usually you have quite a few failures before something starts to work. Furthermore, if you do eventually have a vaccine that works (yay!), you also have to figure out how to make enough of it to use on all the people that want and need it.

Currently, most scientists think that having a vaccine within 12 months is very very optimistic, since they usually take years to figure out. The main difference this time, however, is that there really are a lot of scientists (like a LOT) working on this, so you never know. We will just have to wait, cross our fingers, and see.

5.When will it be safe to go to school?

To answer this question, I want to talk about something called risk. This is basically thinking about the chances of something bad happening. And since we’re talking about chances, it’s actually a kind of math.

For instance, if I flip a coin, and say that a “heads” means that you have to pay me $5, but a “tails” means that I have to pay you $5, you say that there is an equal chance of it being good or bad for you. If we’re talking math and you’ve learnt about percentages, you would say that there is a 50% chance that you will have to pay me!

So basically, the decision to open schools should be based on the math done to calculate the risk. In other words, what are the chances of this being a bad decision.

I live in British Columbia, Canada, and we’ve been lucky because the decision to go back to school is based on a lot of science and a lot of math.

Scientists have basically done math that take a number of things into consideration.

First, British Columbia has a low level of infection right now. This means the chance of meeting someone who has COVID-19 is really small. They can calculate this risk because they have been collecting a lot of data on who is sick and how they got sick for the last couple of months. Note that if you live somewhere else, this might not be the case.

Second, kids like you don’t seem to get sick that easily. In other words, there is less risk for children to get COVID-19 generally. The details for this are being figured out, but it does seem clear that being young, and especially being very young, is a good thing.

Third, it seems that if you have COVID-19, but don’t have symptoms (in other words, you have it but you’re not coughing and sneezing and feeling yukky – or in science words, you say you are asymptomatic), then you might be less likely to make others sick.

And fourth (and this is an important one), you make sure you do the right thing when you are feeling sick. You tell your parents and you make sure you STAY HOME and don’t come to school. You do this, even though the reason you feel yukky may have nothing to do with COVID-19 – maybe it’s just a normal cold. By staying home, you lower the risk of infecting others.

Now for those of you who love math, you may notice that for items 2, 3 and 4, we don’t actually have the exact chances figured out.

We don’t know, for instance, how less likely do kids get sick from COVID-19? Is it half as likely, more, less?

We don’t know for instance, how less likely an asymptomatic COVID-19 person will infect someone else. Is it half as likely as someone who is sneezing and feeling yukky? Is it more or less? Or is it actually pretty much the same?

We also don’t really know how many people will do the right thing and stay home, if they do indeed get sick. Maybe most of them, maybe some of them, maybe only a few?

So, calculating the risk can be tricky.

However, the awesomeness of math, is that you can do ALL the different calculations for ALL the different possibilities, and this is what the scientists in British Columbia have done. Doing these risk calculations for all the different situations, still lead to a risk level that is very low for children in British Columbia.

Now note that this doesn’t mean there is no risk at all. This isn’t actually possible, as there is always a chance that something might happen (think of just walking – the risk is low, but there’s always a small chance you might fall and scrape your knee).

Anyway, even in the worst possible cases, the chances of something bad happening was calculated to be very low, and this is why they felt that it was safe to open schools. Still, this opening is being done with social distancing and all sorts of planning to lower the risk even more. And even with all of this, your parents still get to make the final decision on whether they think it’s ok for you to go back.

But, of course, everyone is watching this very closely.

In the end, this is why you should always listen to scientists (and the mathematicians helping them out). They are really trying their best to give you the latest information and the latest facts that you need to make good decisions.

So don’t forget…